A 'Timely' Letter: Dear Mr Rowlands, Thank you.

Head of Physics Department (likely retired), Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones, Amlwch, Wales, UK

Dear Mr Rowlands,

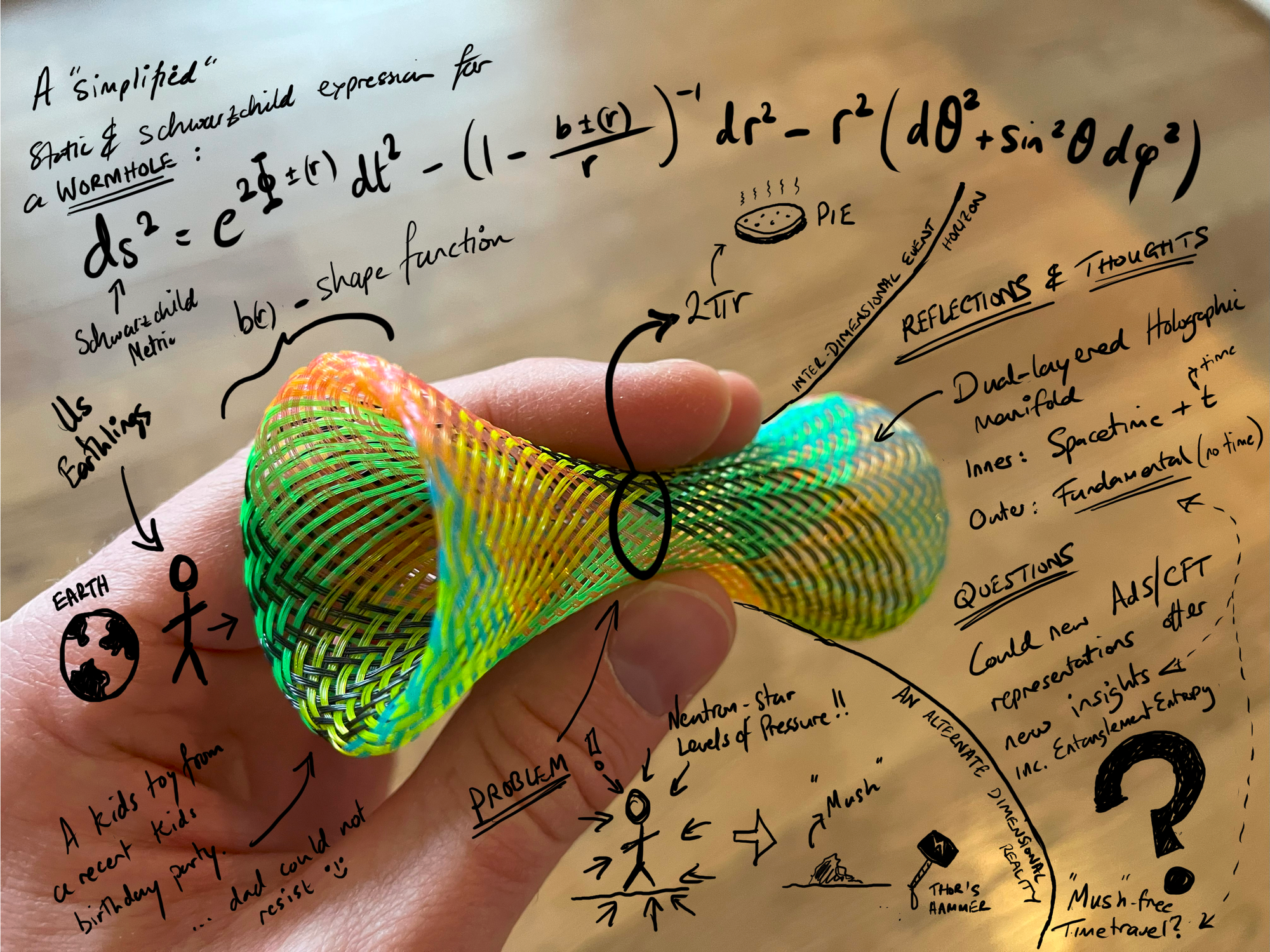

I hope that this letter not only finds you in good health but that it also reaches you. I have been meaning to write this letter to you for some time and I am glad that I finally put some time aside to put pen-to-paper on this matter. A recent toy within a 'goodie bag' that my son received at a recent birthday party, was the final prompting. In this letter I wish to outline my gratitude to you, but I also wish I could have a fire-side conversation with you. Your teaching sparked my passion for Physics, and after a number of years in the 'real world', I have one burning question that I would like to discuss with you;

'If the Holographic principle is proven true, do you believe we live in an inter-dimensional reality and is time travel possible?'

During class all those years ago, we bombarded you with questions, and in fine-form, you elegantly recited the solutions (or thought-provoking questions) straight back at us. But before we delve into this particular question, Nikola Tesla's vision and the potential fractal-roots of the Massey Ferguson logo, let me start with some background.

You may not recall me, but I am one of the many students you have taught over your several decades in teaching. Much like a single strand of silk blown by the winds of curiosity, I don't feel that society fully recognises the transformative impact a passionate teacher, such as yourself, can have on the emerging web of enlightened minds. Your passion for Physics was captivating, and unbeknownst to you, you sowed many seeds in the name of science. For this, I am deeply grateful.

By all accounts, there is nothing particularly memorable about me that can aid the memory here. Possibly only the mere fact that I had a fondness for wearing black corduroy to school, enjoyed playing rugby, tended to stare with my mouth open and had decided against chewing-off half of my school tie. Unbeknownst to me, but this mere carnivorous polyester-ritual was one of the guised trials to determine the worthiness of being called "cool". Having moved to your school during year 8, I kept a relatively low profile in my formative years and quickly realised by year 9 that being "cool" was an enigma that escaped my reach. I was more of a naive spectator of this unreachable state, much like a moth staring at the moon.

Some class subjects, admittedly, were not as engaging as others. From a personal perspective, this was not due to teaching approach, but merely the subject's capacity to illuminate my curiosity. Physics could tell me why the sky was blue and why I could hear the sheep grazing in the fields nearby at night, but not during the day. But my French class was not deemed as illuminative, apart from the ability to decipher Del-Boy's colloquial use of the language whist watching 'Only Fools and Horses' with my step-father. We did after-all live in the Welsh-speaking region of North Wales and my most exotic encounters with outsiders tended to be giving directions to lost tourists looking for the beach in 'Benllech' (which is rather difficult to pronounce correctly for non-Welsh speakers). The B-roads in Wales are notoriously windy, full of humour and on some occasions, contain road signs that rival platform 9¾ at King's Cross station. So it comes as no surprise that I had not met anyone from France until I was at least ten. Unlike the European escapades that my privately-educated university friends had experienced, my school trips lent into more grounded experiences. Our biggest school trip of the year was a 45-minute bus-ride to a carpark outside Bangor to look at the U-shaped Ogwen Valley, accompanied by a brief walk and a ham-sandwich, whilst marvelling at the terra-forming capacity of glaciation. It was simple, interesting and very enjoyable. In many respects, I knew no different and I believe it sowed seeds of gratitude. Anything beyond a sandwich in a carpark was now novel and something to be truly appreciated.

To further illustrate this matter, when I first met my dear wife Cheri many years later, she was wearing a beret and despite her South African accent, I instantly thought she must be French. A few months later, I took her to visit my grandmother in Wales. She was busily plucking a pheasant in the farmhouse washroom and steadily came through, once the kettle had finished boiling on the stove. With tea in-hand and greetings complete, there was the characteristic contemplative 'pause' after a sip of tea, before her first question to Cheri; 'Are there cows in Africa?'. The room fell silent and Cheri realised that day that Einstein was right, time is indeed relative and in some places, it has a different pulse. This reminds me of the words written by Stefan Klein, which eloquently captured our nuanced conception of time, pending one's local culture;

'In Western societies, we measure age by how often the earth has revolved around the sun since our birth. By contrast, cultures that equate age with wisdom are guided by their appreciation of an inner time. Wisdom is defined not by numbers of years, but by experience.' - Klein, S. The secret pulse of time: making sense of life’s scarcest commodity. (Da Capo Lifelong, 2009).

In modern times such as these, the influence of indigenous 'Celtic' cultures of ancient 'Prydain' (the ancient Brythonic name for Britain) has long vanished. These old cultures, like many indigenous cultures around the world, attributed value to individuals based on their inherent value to the collective community, such as the Saint, the Druid and the Bard. This stands in stark contrast to modern times, which tend to attribute individualistic value based on net-worth and equity-enabled 'influence'. However, history informs us that it's the community-inclined and altruistic aspects of a culture, which also resonate with deeper religious beliefs, that survive into the future.

Those who know must be prepared to teach, and use their knowledge in ways that meet community needs...examples abound, from the Sanskrit academies of India to the bardic schools of early modern Scotland, but they share a crucial feature in common. For a cultural tradition to survive...it needs to find a constituency that values it enough to put the survival of the tradition ahead of more immediate needs.

Thus the survival of cultural heritage must draw on emotional drives potent enough to override the tyranny of immediate needs and inspire the modest but unremitting daily efforts needed to keep traditions intact. This is especially true of the traditions of high culture, which often lack short-term survival value and require a sizeable investment of time and resources...

A willing constituency will be hard for any part of today’s high culture to find, and without it, there is a minimal chance that anything more than fragments of that culture will reach the future. Still, there is a wild card in the deck, and its name is religion. Nearly all the classic examples of cultural conservation drew their motivation from religious beliefs.

- Greer, J. M. The ecotechnic future: envisioning a post-peak world. (New Society Publishers, 2009).

It is a curious observation that those authentic 'altruistic' characters, who resided at the periphery of 'normal', can often offer the most insightful wisdom for the future. The curious life of Pelagius and incredible ingenuity of Nikola Tesla reflect this in the most succinct manner; they were both in a sense "counter-cultural" and "different" during their respective lifetimes.

'It is understandable how the teachings of Pelagius, who celebrated all of creation—each person, animal, fish of the sea, bird of the air, tree in the forest as possessing a part of God rather than merely being created by a God who then backed away from the creation, so to speak—was considered . . . different. And different can so easily and so often be misunderstood.' - Jordan, R. The ancient way discoveries on the path of Celtic Christianity. (Broadleaf Books, 2020).

Since then, there has been an earnest revival of interest in the technological accomplishments of Nikola Tesla and in his personality, philosophy, and culture as well. Part of the drama of his life is that he was a man who not only revolutionized the generation and distribution of electrical energy and made basic contributions to many other facets of modern technology but that he did so without the specific aim of amassing great wealth. This altruism, which is often criticized as “poor business sense,” imposed a monetary limitation on future experimentation to test his new innovations. Who knows what advances might have been possible if he had been able to validate them through rigorous experimentation. New science is an expensive endeavor, and finding financial support is a frustrating task for even those as focused as Tesla - Seifer, M. Wizard: the life and times of nikola tesla. (Citadel Pr, 2016)

Given the current challenges of climate change, the prevalence of pollution and unsustainable industrial practices, Tesla's outlook on life will resonate with many who have altruistic inclinations.

Clearly, Tesla was, in some sense, a revolutionary and on the side of the worker, but more for the purpose of transforming and uplifting their station. Tesla’s inventions were purposely constructed so as to reduce consumer cost, preserve natural resources, and relieve humanity of unnecessary manual labor. Seifer, M. Wizard: the life and times of nikola tesla. (Citadel Pr, 2016)

In similar fashion, my respect for my grandmother was due to the deep-well of experience that she embodied. My grandmother was a remarkably resilient woman, having raised six children and ran a Welsh hill-farm alongside my grandfather. As a parent of three myself now, I often wonder how on earth she managed to parent, walk a few miles to the closest post-office, fetch water from the local spring, cook, mend clothes and care for some animals (such as the lambs and chickens). In those days, admittedly they were not as well-travelled, but they had cultivated a range of home-making and crafting skills that would shame most modern folk. The likes of Bear Grylls and Ray Mears representing the exceptional minority here. The farmers of her generation were remarkably resilient and self-reliant. In some respects, her world seemed both simpler in purpose but more exposed to nature's whims, which is an appealing paradox. Here resides a curious lesson of contrasts; herding sheep from the high-moors on foot with a sheepdog in the driving-rain relative to being in a warm 4x4. The farmers of past generations were a hardy folk.

'It took traditional communities often thousands of years to learn by trial and error how to live and farm within the constraints of tough environments like ours. It would be foolish to forget these lessons or allow the knowledge to fall out of use. In a future without fossil fuels, and with a changing climate, we may need these things again.' - Rebanks, J. The Shepherds Life: A Tale of the Lake District.

Looking back now, as someone who has lived in several countries, there was a refreshing innocence within a simple childhood. Something I wish for my own children, but this is still a work-in-progress plan. This sheltered childhood had not imbued within me the nuances of the global cultural spectrum, but the sowed humility of a rural up-bringing meant that I approached novelty with a sense of wholesome endearment. Much like my grandmother's first question to Cheri. This wholesome endearment very much captures the essence of what you instilled within your students, Mr Rowlands. In this sense, I am very thankful to you, you were always patient with all of us in class (despite our varied backgrounds), as you carefully opened our minds to the magical world of Physics.

Day-dreaming in class had become an art that I sought to refine during my schooling years, since for much of my younger years, I just wanted to be a farmer. The farm was far more adventurous and appealing than a magnolia classroom. To know about geometrical constructs, such as certain fractals, was useful to a certain extent; such as recognising that the Massey Ferguson badge on our tractor was possibly inspired by a Sierpinski triangle.

But beyond that, it's capacity to illuminate my chosen path in life was limited (well, so I thought). Unfortunately for myself, a fully day-dreaming state was not conducive to learning, hence this skill had to be refined to a middle-ground of "deep consciousness" but also partly absorbing the influx of information during class. This came together a little late for myself and my GCSE results were on the upper end of the entropic scale. After all, heterogeneity and multiplicity are far more reflective of our world, which dances to the paradox of entropy and interconnectedness.

However, during that subsequent summer of 2003, something happened, and until this day I do not know what exactly transpired. All I remember is that I slept a lot, grew a lot and needed to buy longer trousers. I looked like a stork in shorts and my new nickname post-GCSEs, coined by my friend Sion, became "stretch". But more so, all those years of sitting in the third or second row of your Physics class, the seeds of information were starting to root and make sense. I became very curious about how the world worked and your passion for the subject was captivating. You also consistently wore a black suit and a white shirt, even the "cool" kids listened to you, and somehow, this manifested an air of mystery about you. Having recently read a book titled 'The Art of Gathering', your consistent attire and consistency in greeting your students at the doorway became the threshold which our minds would learn to recognise, whereby one felt a sense of 'belonging';

'The idea of helping people transition from one state to another is embedded in many rituals of traditional societies. It’s the equivalent of a doctor taking off her jacket and putting on her white coat as she enters her office. It’s the act of Muslims washing their hands and feet before prayer. It can be the removal of shoes before a Japanese tea ceremony. The only difference with modern gatherings is that the passageway is not prescribed. You need to create it. And one of the easiest, most natural places to create such a passageway is the doorway.' - Parker, P. The art of gathering: how we meet and why it matters. (Riverhead Books, 2018).

I remember thinking one day that you could have been an Paratrooper prior to teaching, since even in heated classroom scenarios, you always remained unnervingly calm and collected. You were a true master on the use of reflective silence during public debate (your booming voice also likely helped emphasize the dichotomy of this approach). Thanks to your gifting as a teacher, my passion for Physics was now well on its way down into the valley of higher education, driven onwards by the gravity of my own deepening curiosity. I attribute the source of this metaphorical spring to be the work of your engaging teaching and how you sparked an interest in Physics amongst myself and my friends. Fortuitously, my mathematics GCSE grade was good enough so that my mother could encourage the school to allow me to continue into A-levels with Physics, despite not sitting the highest paper (I received 98% and 100% in both math papers, but could only maximally achieve a B, given my class allocation in earlier years). However, I had to catchup on the material I had missed having not been in the top sets in recent years.

I was very much what they often call a 'late bloomer', which is a term I am not particularly fond of since I think all folk 'bloom' in their own unique ways and timelines. I often feel that our stage-gate and prescriptive approach to education can often not accommodate us 'day-dreamers' who reside at the periphery (apparently the term 'neuro-divergent' is used today, apart from knowing how to spell that, I don't know much more of what the term entails). My 'F' GCSE grade in Welsh Literature was not purely attributed to the fact that I had barely read the course book, but also my apparently curious tendency to spell words in the incorrect order. Luckily, there were no consonants and vowels in Mathematics. But let's just say that my curiosity in the natural world and the cosmos experienced a sudden seismic shift at the very mid-point of my teenage years. Something I attribute mostly to you Mr Rowlands and another Feynman-like tutor, Zahir.

This extra challenge of catching-up in Mathematics provided me with an opportunity to meet an other remarkable individual, Zahir. I believe Zahir originally came from Iran and he was likely one of few with such middle-eastern origins in our small rural village of Llanerchymedd. Like many parts of Wales and New Zealand, sheep do outnumber the local population around these parts of the world, so the locals had to content themselves with one snooker club, a grocery, a church and a pub. Likely an honest reflection of supply and demand.

I unfortunately cannot recall where Zahir studied Mathematics, but all I can say is that he truly grasped Mathematics as the language of the cosmos, his passion paralleled yours Mr Rowlands. I now know that Iran is rather famous for producing mathematical prodigies, as exemplified recently by the late and remarkably humble Maryam Mirzakhani. Much like how a bat navigates the abyss by sound, some numerically inclined individuals perceive the world through the aperture of mathematics. To people such as Maryam Mirzakhani, Richard Feynman and Roger Penrose, mathematics is as natural as sight and they can effortlessly relate complex concepts through artistic constructs and conceptual analogies. I recall sitting by the window in Zahir's house, working through mathematical topics. Due to his amazing teaching ability, I won the medal for Mathematics in our A-Levels year. I say this to merely reflect the impact an impassioned teacher can have on a willing student, and his efforts certainly aided my comprehension and appreciation for Physics. Zahir, if this note ever reaches you, I extend my heartfelt thanks.

This brings me to a final remark about your holistic teaching approach. You created an environment that was conducive to learning. This was not a matter of owning the latest laboratory apparatus or large school budgets, but rather, the softer aspects of 'cynefin'. There is no English word that can fully captures my point here, but I know that you are familiar with this Welsh word. Here, I would like to reiterate two examples. Before going into these two memories, I should also at this point note that the Sir Thomas Jones School was historically designed as a large hospital. It looked like an over-sized albino telephone-box, characterised by high-ceilings, square-corners and very large windows. I liked it.

Admittedly, it was one of those places that felt grandeur on the inside rather than the outside. Being painted white also had its practical benefits, since the artistic defecation efforts by the local seagull population were rendered invisible to the eye.

Recollection 1: My first collection where you created an environment where the mind was allowed to truly wonder and you let silence run its course. We were all in the back-room of the class (which was enormous, despite the name), all huddled in the dark around an ambient light and a diffraction pattern. All the students hanging on your final remark on the experiment, 'you as the observer influence the outcome, such is the quantum nature of light'. What?! The silence in the room held all in suspense. The questions came reeling in, 'but what about starlight?'...

Recollection 2: My second recollection was when myself and some friends had received our A-Level results and were talking about a coming televised rugby match, debating the outcome and the form of certain players. I cannot recall what we wanted to give you, but we agreed to meet at yours to give you a gift. You greeted us into your home and we talked a little about the rugby and recent progress in Physics. You were relatable, approachable and also had to do the 'mundane stuff', such as taking your car for an MOT.

I would like to close this letter, with a mnemonic I recall from Mr Roberts's (another brilliant teacher at the school) mathematics class on Trigonometry;

'Silly Old Harry Caught A Herring Trawling Off Anglesey' - Mr Roberts, Mathematics Teacher

Who knew SOHCAHTOA could be made so locally relevant.

I now feel like that 'Herring' who left Anglesey, lured away by my own path in applied physics. If I do ever return to Anglesey in the near future, I will certainly drop a note to the school (I hope that they still have your contact details). It would be lovely to catchup for a coffee. I would very much like to hear your thoughts on the plausibility of inter-dimensional travel ('time' inferred here) within the context of the Holographic principle.

This letter is a snapshot of how you shaped the life of one person and I'm a mere 'Herring' amongst the ocean of students you have influenced. In this respect, much like the criticality of a keystone species (such as a Beaver), whom have a disproportionate influence on their environment, I do wonder why teaching is not recognised on parity with professions such as Surgeons and Barristers. Societies ought to follow Finland's example in its recognition of the teaching profession and 'unshackled' approach to education. The children of tomorrow would all benefit from more equality in education. To close, I would like to leave a note by the brilliant Raymond Williams, who, much like yourself, recognised the nuanced reality of growth, flame of curiosity and the critical role of environment within the broad spectrum of formative education.

To take intelligence as a fixed quantity, from the ordinary thinking of mechanical materialism, is a denial of the realities of growth and of intelligence itself, in the final interest of a particular model of the social system. How else can we explain the very odd principle that has been built into modern English education – that those who are slowest to learn should have the shortest time in which to learn, while those who learn quickly will be able to extend the process for as much as seven years beyond them? This is the reality of ‘equality of opportunity’, which is a very different thing from real social equality. (Raymond Williams, 1961/2011:177) - Menter, I. Raymond Williams and Education. (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020).

Until a future time Mr Rowlands, take care and I hope retirement is treating you well.

Yours faithfully,

Aaron